Description

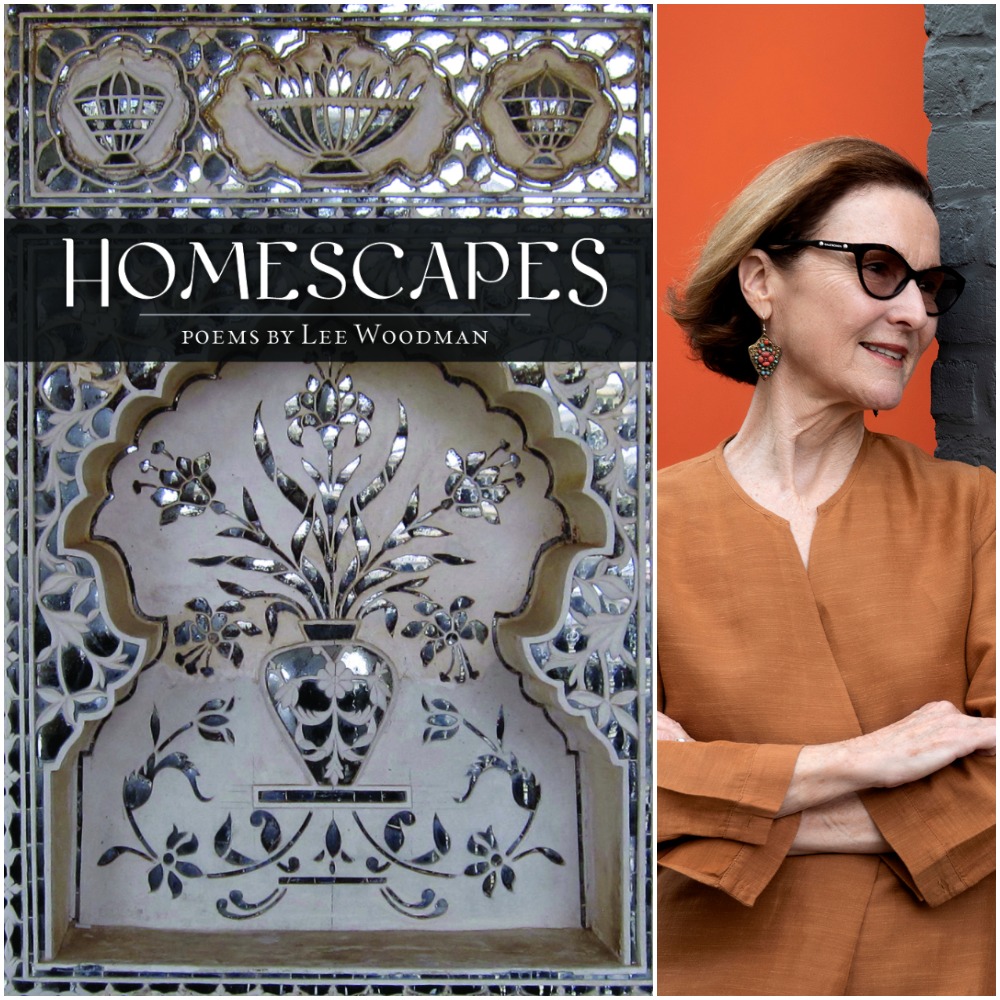

HOMESCAPES

by Lee Woodman

$19.99, Full-length, paper

978-1-64662-213-9

2020

Home is a relative term, especially if you have grown up overseas. In HOMESCAPES, Lee Woodman takes us from an Indian village to the edge of Tibet to a small town in New Hampshire. An audience with the Dalai Lama touches her spirit; questions from an American high school homeroom teacher challenge her wit. Lee never stops searching for what it means to be American, digs deep to understand her New England roots, and ponders intimate relationships, persistently asking, “Where—and what—is home?”

Lee Woodman is the winner of the 2020 William Meredith Prize for Poetry. Her essays and poems have been published in Tiferet Journal, Zócalo Public Square, Grey Sparrow Press, The Ekphrastic Review, vox poetica, The New Guard Review, The Concord Monitor, The Hill Rag, and forthcoming in Naugatuck River Review. A Pushcart nominee, she received an Individual Poetry Fellowship from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities FY 2019 and FY 2020. Her poetry collection, Mindscapes, was published by Poets’ Choice Publishing in February 2020.

Susan Snively –

As I began to read Lee Woodman’s dazzling new book of poems, the title leaped out at me, as if to deliver an urgent message. The word held other words inside: “me,” “escape,” “scapes,” “hope,” and others. I saw safety and danger traveling together, as “home” brings forth new “me-scapes,” versions of herself speaking new words: “nullah,” “peelu,” “dhobi.” Woodman’s vivid, sensuous language draws on the poet’s experiences living in India, France, and New Hampshire. As we read and re-read, we discover how the road to home may become both escape and return. Her skillful handling of form and rhyme (free verse, syllabics, villanelles, hymn meter, among others) creates a template for memorable images, like the “voluminous Hemlock” that “absorbs all life’s events: attacked, endured, sun saluted, sorrows sustained.” (“Trees have Longer Lives.”)

The book’s three sections, “India,” “America,” and “Stereoscope,” recapture the many awakenings of adolescence in a faraway place, in company with her family. In “Road Trip to Nilokheri” she travels with her father through “wobbling air, ” “ripples of cool from the nullah’s water” battling “currents of heat that flare down.” When she plays with the local children, she fumbles the ball, but they giggle and the village elders “salaam, pressing palms together—Namaste.” The poem touches on awkwardness, then eases into a tone of gratitude for small comforts, “A weak trickle from the shower,” the taste of “our surviving cucumber—melony, slightly sweet, faintly salty—the last warm coke, delicious.” This is no supermarket cucumber, but a vegetable with a complex nature.

In “Jaya the Ayah,” the rhymes—“vinegar, “”sinister,” “blood,” “commode,” suggest the Ayah’s venomous behavior toward the sisters and her own boyfriend (“Snap! She broke his bone in two”). When they learn that Jaya has been “fired,” the girls, “terror-struck,” take the meaning literally, “horrified to think / she still lay burning on her pyre.” The poem places troublous imagination at its center. Woodman blends the perils of the world with its edgy pleasures, as in “Climbing the Rohtang Pass.” On the border of India, the Rohtang Pass, flanked by forests, “rocky rubble,” and “jagged peaks,” means “Pile of Corpses.” A photograph taken by her father shows her in the Pass, in mountain clothes, but lifted aloft into China, where she imagines “those frozen souls below / had chosen to stay there.” In the last two lines, the poet rises up into “an endless view” that “could drown us all–/ a sensation of snow under our bellies for the rest of time.”

Woodman’s ease with internal rhyme shows up in various ways: “Homeroom Ghazal” uses the word “home” as “a relative word”—one of her puns. While Lee and her sisters prepare for sock hops by listening to rock ‘n’ roll on WBZ, their mother, who had “twirled in silver purple taffeta” at glamorous parties in Delhi, watches “As the World Turns” on “our first-time-ever TV.” The details of daily life, like her father’s Old Boston pencil sharpener with “its roundabout of multi-sized holes,” (a playground ride transported to a desk) complicate and enhance the “homeland” the poet shares with “a flock of purple finches” who write their own stories with “Quills tipped in raspberry.” (“Father’s Roll Top.”) What the poet calls her “inherited irreverence” begins a poem (“A Mulch Pile Prayer”) on a wacky note: “Our Father who art in the mulch pile, Hallowed be thy Brussels sprouts.” Several poems in this “America” section of the book have an elegiac, yet wry tone: “Found in a New Hampshire Cottage” ends: “Years later, there is still an urn we plan to bury sometime.” No guilt trip, just a wish as yet unrealized.

In the book’s last section, “Stereoscope,” the poet completes the ritual of burying her parents’ ashes in the Ganges (“Visit to Varanasi Forty-Seven Years Later”). Helped by her guide, Bena, she learns that “miniature clay lamps can be set free in the black water, a holy way to bid farewell to he dead and dying.” Her father’s lamp holds a candle. As he “forms his own vanishing stream in the current,” the three yellow marigolds for her mother “follow swiftly, forming rivulets back and forth across his wake.” The poem’s sinuous long lines recreate the stream and the rivulets that vanish, but like gifts from the depths, they bring back flame and color. Such images are memory’s afterlife.

Susan Snively

https://susansnively.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=46&Itemid=54

Tanner Stening –

Every so often, there are poems that come together in a single volume to depict both the exotic and the ordinary places one gets to call ‘home’ during a lifetime. Not only does Lee Woodman’s Homescapes render these formative places—parts of India and New England, to name a few—with fine lyrical detail, but she returns to them after decades have passed with the clarity of their assimilated meanings. She returns to them with an artist’s understanding of their value to a life.

I met Woodman at a writers conference in New York City in 2018, when many of these poems were under construction — or better put, under refinement. At the time Woodman had few poetry publishing credits to her name; but it was clear that the poems she had been working on then had already reached a maturity of expression. They were musical, elegant, with joyous debts to Modernism’s singsongy forms and rhythms. Some two years later, Homescapes would go on to be selected for publication by Finishing Line Press—just several months after she won the 2020 William Meredith Prize for Poetry for her debut collection Mindscapes.

Homescapes is a look back at a lifetime of relocation—at the indelible moments and impressions, from preadolescent infatuation “at the American Embassy in New Delhi,” to an heirloom necklace “studded with rubies” left to the speaker, who first saw an Indian jeweler sketch the very gems sixty years ago as a child living in India (though she is American). In “Ruby Necklace,” she dons the precious stones in Washington, D.C., all those years later—a gesture that speaks to the durability of memory, and to the storied journey of objects: “I wore it to the Kennedy Center not long ago, rubies cascading / Down the deep décolletage of my green silk dress / Pearls spreading across frosted gold branches, / Diamonds aglow, I was almost…”

But relocation comes with risk, upheaval, alienation. In the first section of the book titled “India,” the speaker recalls a nanny who threatened to lock her in the bathroom “and dangle red chilies / across my bare labia lips.” In a later poem in the section, she remembers riding her first bike and confronting a rabid dog, and even later, in “Climbing the Rohtang Pass,” which is a meditation on those who didn’t survive the perilous journey through one of the world’s most dangerous mountain passes: “I felt airborne into China, hovering over mounds of ice. / Perhaps those frozen souls below had chosen to stay there. // The rush of wind, vast endless view could drown us all— / a sensation of snow under our bellies for the rest of time.” Our 12-year-old year speaker, even then, “understood how daunting the climb.”

For Woodman, the drive to inventory the central places of one’s life is not about collecting souvenirs; nor is about revision—the fictionalization of one’s past to suit an illusory sense of self. No, Homescapes is about illuminating the past, preserving in language what is essential to one’s particular understanding of oneself. Therefore, description becomes elucidation; the act of rendering the irrepressible details of what lives in memory, for Woodman, is a life-giving exercise.

And Woodman’s descriptions, her ability to recollect at tremendous depths—become reimmersed in memory’s sensuous ingredients—combined with her lyrical ear have made for many compelling poems in this collection. From “Trees Live Longer Lives,” a poem in which the speaker attributes a profound wisdom to the lone “voluminous Hemlock on my mountain”:

“What we pass fleetingly, the wizened one protects:

boisterous bickering of blue jays and squirrels;

black bear with brown muzzles, growing fur for the season;

Siberius Iris, bursting perfume through raindrops;

overjoyed children, galloping with laughter;

sad conversations between lovers no longer.

The Hemlock absorbs all life’s events:

attacks endured, sun saluted, sorrows sustained.

Its supple trunk carries the load, leaves clapping their memories.

I hope never to witness rings or scars,

but to revel in its graceful branches reaching ever higher, blowing us messages.

For my revered tree will have longer thoughts than we, and

longer longings.”

Homescapes is also a moving tribute to family—to the speaker’s parents, who are the source of many tender and heartfelt singular poems. Woodman writes about them with clear-eyed appreciation, humor, and compassion, from their early presence in the “India” poems, which are filled with discovery and adventure, to their later decades of decline. Her father, a World War II veteran who first initiated her into travel, is in a later poem hunched over a roll top desk, working in vain to give shape to his own experience in words: “He glares at the blank page, / swears when the pencil breaks again, / sweeps the paper stack away.”

But Woodman does not fall victim to this particular silence, though it is clear from this distinguished second volume of poems—poems that are at times rapturous, gusting with the velocity of years and the sensory data that spills from them—she is empathetic to those who’ve suffered speechlessness. Homescapes is a testament to the perseverance of the writer and what lives on, ineradicable, in the writing-consciousness.

—By Tanner Stening, Poet and Journalist, MassLive