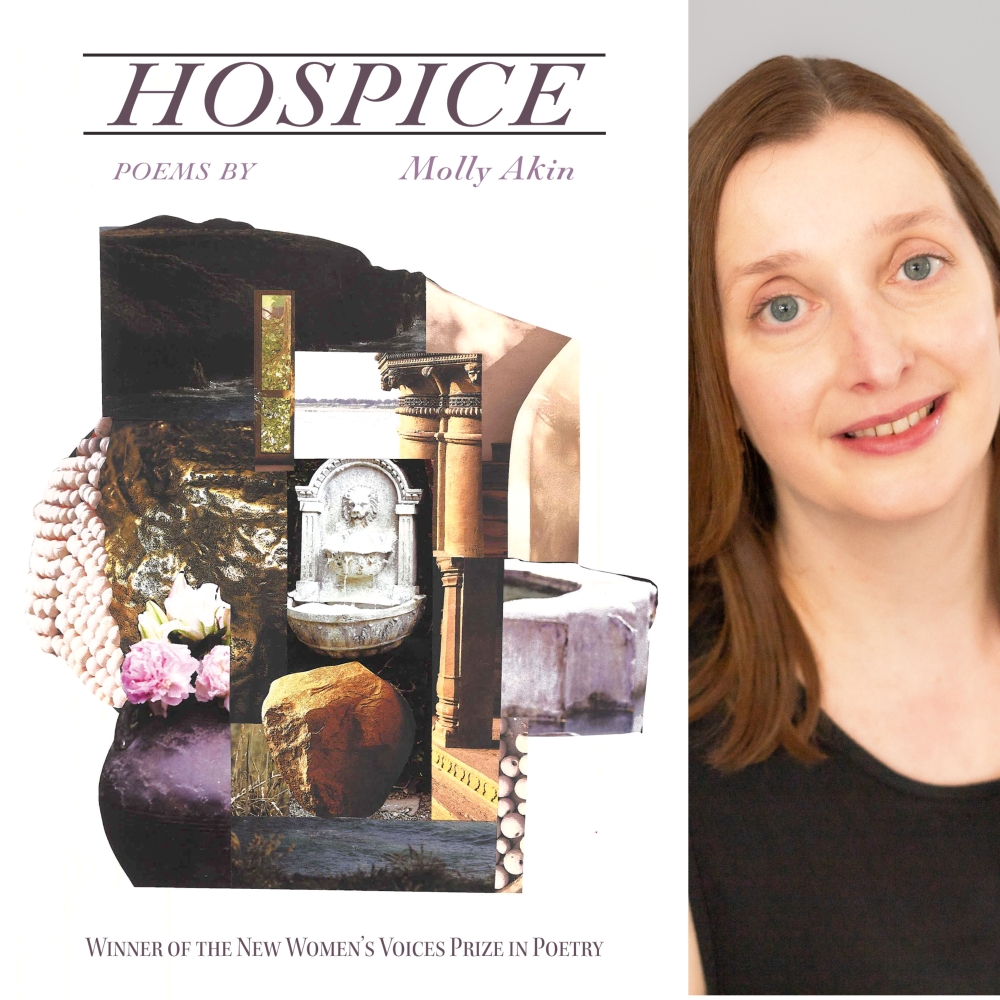

Mothering, compassion, lineage — Akin explores the mega sphere that is contemporary motherhood in this striking chapbook collection. In a lean but hard-hitting, visceral verse, Akin ardently depicts what it is like dealing with the loss of a mother, void and haunting memory. A strong, memorable debut collection!

–Jose Hernandez Diaz, author of The Parachutist and Bad Mexican, Bad American

Molly Akin‘s Hospice unearths the hidden beauty and devastation at the root of grief. From the life cycles of ladybugs, orchids, and loved ones, Akin offers a meditative glimpse into the ephemeral nature of living, the consuming nature of loss, “the keening cry of a bird,” and “the waters no damn can hold.” With lightness and depth, this collection unravels the sacred contradictions that sustain us, the ones embedded in being alive, of mothering, of losing and loving, again and again.

–Tatiana Johnson-Boria, author of Nocturne in Joy

Its title suggests, Molly Akin‘s debut chapbook, Hospice, is about end-of-life care––a poet bearing witness to and participating in her mother’s final weeks and days––but the etymological root of that word, the Latin hospitem, meaning “guest, stranger, sojourner, visitor,” is also very much at stake. In these poems, the reader sojourns across a defamiliarized world, acutely described with a Dickinsonian economy and cataloged, freshly, by Akin’s fine-toothed aesthetic. Akin’s is not the language of life but the language of death, of near-death and after-death: that fragment, or moan that is whispered across the “gash // wound” between the living and the dying (for in Hospice, there is nothing so gentle as a “veil”). As her mother dies from a long cancer––”spider pain / leg pain / bone pain,” her “tail / tucked / between / bone”––the poet dares also to look closely at her own flesh, her image a “coiled / Siren,” her body also a mother’s body, aging, resilient, pained, ancestral, capable, moving through time: “One big contraction,” she writes, “And it is our life / Looking back.” But for as much as this book looks back––and it does, at the poet’s origins, at language’s deep lineages, at Dickinson herself––it also gazes forward, toward a world marked by new absence and yet newly possible. “It took her / death / to wrest / my self // from / her––,” Akin writes. And that is the difficult space where these poems sit vigil: bedside new knowledge.

–Jane Huffman, author of Public Abstract

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.