Description

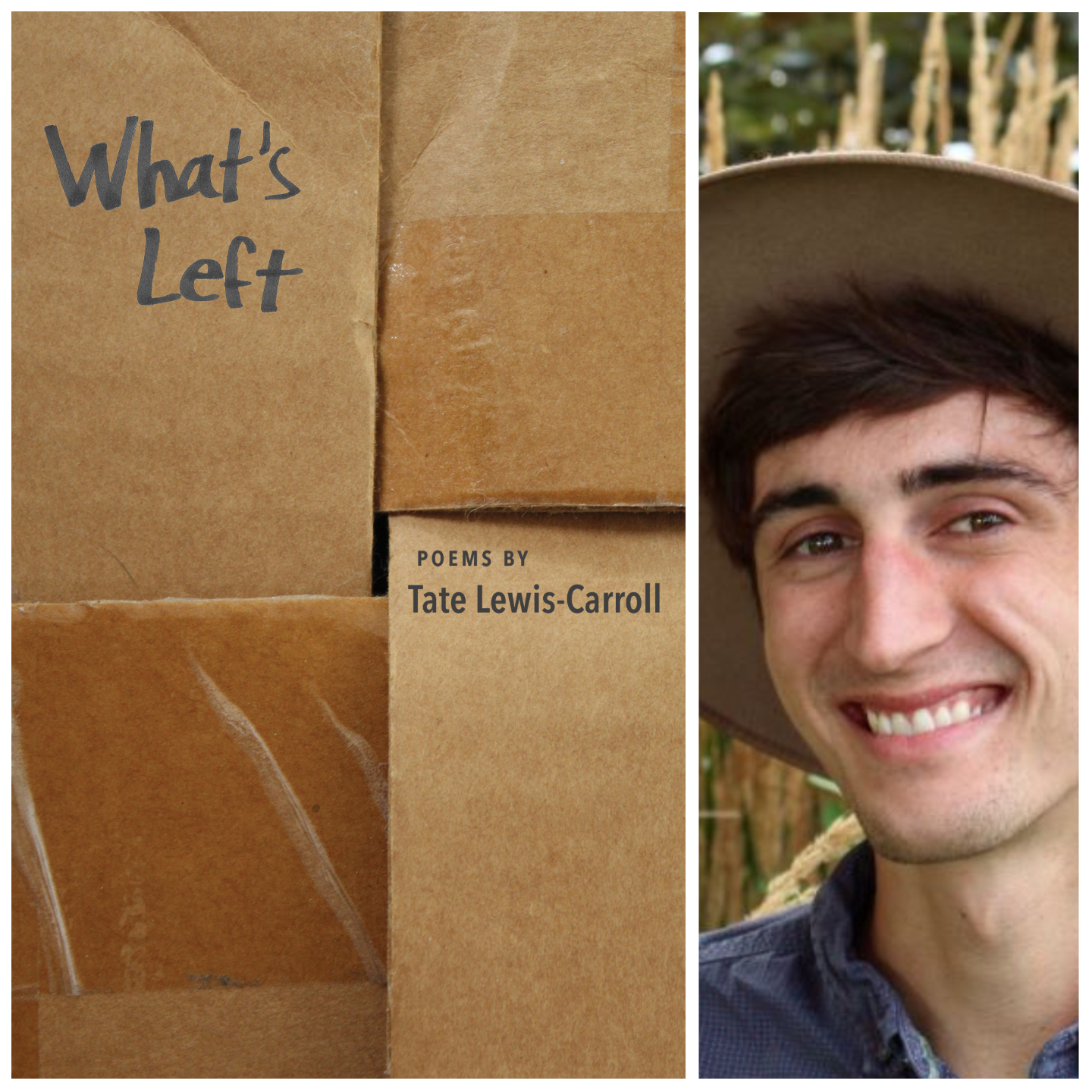

What’s Left

by Tate Lewis-Carroll

$22.99, Full-length, paper

979-8-88838-078-9

2023

What’s Left is a living record of Tate Lewis-Carroll’s dying father and the often estranged but sometimes idyllic relationship they shared. As urgently as the initial cancer diagnosis and death six months afterwards, this project began with startlingly raw poems written beside the father’s deathbed. Yet, upon uncovering the father’s wide-ranging nature photography, Lewis-Carroll is able to reexamine and finally relate to him in a way that had seemed unreachable in life. Obsessed by this act of excavation, Lewis-Carroll unpacks every eclectic box in an attempt to discover what’s missing, what’s sincere, and what’s left after death.

Tate Lewis-Carroll (they/them) is the editor of The 2022 Texas Poetry Calendar, serves as Poetry Editor for the Ocotillo Review, and edits for Kallisto Gaia Press. They’ve lived most of their life somewhere in the Midwest and now reside on a small farm in rural Illinois with their photographer wife, Izzy, and many animals. Find them on Instagram @tatelewiscarroll Twitter @tplpoetry or somewhere out in the woods, reading.

Sarah Elgatian –

What’s Left (Finishing Line Press) builds its atmosphere immediately — the cover and epigraph synching an ambiance by opening with a formally stylized Nirvana quote followed by a transcription of a sparse voice message from the author’s father (the cover is a cardboard box with the top folded shut, it’s labeled in permanent marker with the title). The foundation indicates elegy — and the book is an elegy — but the scaffolding suggests renaissance, too.

I have been around death a lot and often find art surrounding it either flatly grim or trite. Tate Lewis-Carroll’s poems are neither. They stick to your ribs and wind around your ankles, weighty and precise. While the speaker grieves their father’s death, they take the reader’s hand and offer us the room to grieve, too. We watch the father from a child’s point-of-view, awe-struck, in the opening poem, “Shell Collecting,” a father and child digging for shells: “like the right word for a poem: precious wentletrap, / lettered olive, moon snail. He’d recall their names / as if he were the one who’d lost them.”

The first poem introduces the cancer the father will eventually die from, but slowly, after we witness the relationship between father and child change and strain. Interspersed between poems that indulge difficult memories are six poems titled “At My Father’s Wake,” each with a parenthetical subtitle that could be funny, but mostly hit close to home (I feel confident anyone who has ever been family of the deceased knows this experience) including: “An Exhibit Where Strangers Stick Their Fingers in My Cage to Feed Me Their Opinions Disguised as Pieties” and “A Causeway Toll for which Passersby must Scrounge for Spare Remarks In Order to Leave the Island” and “An Arcade With Only Whac-A-Mole Machines.”

This exploration of death and grief is, like all explorations of death, also an investigation into what it means to be alive — and to live with death. This painful duality is expressed in “Another Cherry Tree,” with a line that resonated with me enough to cause me pause, “Their bodies / will / sprout up / all around you like thistles / And like thistles / they will cling to your socks / and leave little splinters in your fingers, / which will linger all day / when you try to pull them off.”

There are many more excerpts I marked to quote here, dizzying concrete poems and clever uses of form (haiku and sestina!), but I would be remiss not to mention the bright color photos that act as section dividers. Given the attention they deserve, they are another powerful illustration of life in stages.

This collection provided me with great catharsis, a feeling of being seen. After many times bereaved and having no language to express it, this book is a gift. It conjures words from our most vulnerable moments — “And what a jealous god / it is, always taking, taking. / With a jealous god come commands, / come severed limbs, come rivers / of blood, comes seeing the devil’s hand (from “The Anatomical Man”)” — and gives us something to do with them. There’s an annoying stereotype that says that pain is a catalyst for art. I have found that untrue, but with this book came a reprieve. This book made me want to create.

This article was originally published in Little Village’s February 2023 issues.

Claire Younger Martin –

What’s Left and Learning to Exhume Softly

In their breakout poetry collection, What’s Left (Finishing Line Press, 2023), Tate Lewis-Carroll beckons us along as they begin the harrowing process of rummaging through their late father’s life in images. Opening while their dad is still alive and receiving cancer treatment, we meet a man who is simultaneously foreboding and careful, a bit of a mystery like many of our parents can be when we’re young. But then he dies, and we must meet him all over again. Collected between Lewis-Carroll’s dreamlike poetry and a box of photographs their father leaves behind, the heart of this work lies in the complexity of character it presents us all with. They stand as the perfect guide as we watch them spend their young adulthood grappling with the seemingly insurmountable task of learning who their father was now that he’s gone.

Throughout this collection, Lewis-Carroll lends their father the rare opportunity posthumously to narrate his own story. He comes alive for moments at a time alongside Lewis-Carroll’s telling through inclusion of his photographs and snippets of conversation between his old friends at his wake that strike first as disarmingly funny, then fade into a sting. The space between these pages is so private that we feel especially privileged to be invited into the conversation between father and child. As the collection unfolds, there’s an increased sense of intimacy as we move through forests and hospital beds, rivers and cemeteries. Their natural eye comes to the forefront especially in Practice: Haiku where we watch vignettes come together over these images.

“red sea

rushing back

to the heart

–

at lunch,

nursing students practice

on an orange”

This feels like a sigh and a nudge onward in the collection, generously allowing us to shift our perspective of this grief by zooming in and out. We see more of this in Memorial Day when we watch Lewis-Carroll silently take stock of the spiritual beliefs they were raised with while visiting a graveyard. They gracefully subvert sorrow’s chokehold and we’re left feeling at ease as they find solace in the long shadows and wind, both things missing from the stark inside of something like a mausoleum. In these observations, we’re invited to expand our close examination of mourning outward again and again. The shared language between Lewis-Carroll and their father exists in these pockets of nature, always bringing us back to a moment of precious life. The two seem to be locked in a game of chicken, both challenging one another to dig deeper into their shared story. It builds into something deeply satisfying by the close, touching us with its candor.

Moreover, it’s hard to find works that deal with discovery in loss with as much care as What’s Left. Lewis-Carroll allows us to meander through the pages, as though each heavy blow is followed by an equally fresh breath of air. Nearing the end of the book, they give us Another Cherry Tree. In this poem, they find that the towering memory of their father sprouts up in their yard one morning as a vindictive and taunting sapling, and to carry on with their life they must hack him down in a blur of blood and tears.

“The night is growing green with dawn, the ground dews,

a chill fogs between us. Viscous, sappy blood

crystallizes all down my arms and hands.

My legs tremble with exhaustion,

but still I charge him.

Morning comes fully now,

he’s teetering on a single stilt,

the sun rises like a guillotine.

To make a long story short,

I fell him.

He splinters.”

We’re left in quiet reflection as the dust settles when Lewis-Carroll offers us an exhausted and somber final sentiment, “Do not resurrect your dead.” Then we turn the page and are immediately met with one of their dad’s photographs, a sky so cloudless and blue, flawlessly orchestrated to leave us in awe of the kind of person who might stop and capture one of life’s simplest pleasures, then save it for his children to find. This perfect whiplash is the true constant of this collection. Lewis-Carroll is always sure to bring us down to the depths with them, then look back over their shoulder to make sure we’re able to come up for air from time to time. It’s conceivable that this is a precise reflection of what they experienced in their father’s living years, creating an endless cycle of fury and tenderness. In answering the question that the title of What’s Left poses, we watch a young Lewis-Carroll muster up the strength to discover that both can coexist in a father.

At its core, What’s Left is an offering. Reverent and massive in content, it’s a gift that reminds us to not be afraid of finding the fullest stories of those we’ve lost, and filling in the gaps ourselves when need be. Lewis-Carroll’s writing is teeming with wit and yearning that works as an undercurrent, drawing us all deeper into the heart of their collection. The poetry itself is playful and physically expressive, an exceptional pairing with Lewis-Carroll’s wildly engaging eye for value in everything they see. Shell Collecting meets us at the very beginning, illuminating this straight away.

“In the still forming twilight,

his hands would hover above the water,

swinging the flashlight, searching–

Suddenly they would dig,

sift, pluck, and cradle shells that hid from us

like the right word for a poem: precious wrentletrap,

lettered olive, moon snail. He’d recall their names

as if he were the one who’d lost them.”

Nothing is overlooked in this narrative, and they stand as the steadiest vessel for the echoes of their father to speak through. As their two voices come together, both commanding and inquisitive of one another, the book becomes impossible to put down. When What’s Left is handed to us, we have no choice but to accept it with as much poise and urgency as it exists with.